Last Call: Prohibition in the Valley

almost a century ago, wets and drys battled on cultural lines over prohibition in the Chippewa Valley

Andy Hanson, Caleb Gerdes, photos by Chippewa Valley Museum |

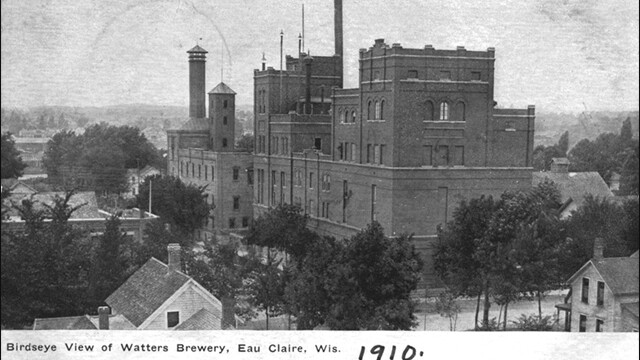

The Chippewa Valley has a rich and frothy history when it comes to beer and other alcoholic substances and the breweries and saloons where said substances were, of course, fermented and imbibed. In fact, if you happen to pick up a good ol’ Leinenkugel’s sometime, you’ll be drinking in historical fashion. The brewery based in Chippewa Falls proudly displays its birth year, 1867. Current culture and practice in the Valley has us tipping barmen and barmaids while toasting friends and frenemies and the new dude you just met while waiting for your favorite frothy beer to make it down the line to you. Replace the booming music and the TVs with a few gentlemen in the corner with fiddles, a piano, and gratuitous mustaches, and the sights and sounds of the saloons seem to have flowed uninterrupted from past to present. However, there was a time when the taps ran dry and the glasses grew dusty. The national Prohibition campaign succeeded and thrust the Chippewa Valley into an unexpected dry spell. This well-known period of national history had a significant impact on our favorite place to live.

The Foundations of the Valley’s Boozy Culture

As North America was explored and settled, European culture was transplanted to this fertile and exciting soil. The prospect of living in a new land and building a new life was undoubtedly less daunting with a few drinks, and what’s more comforting than enjoying the drinks and dishes of your homeland? When moving to the New World – well, New-to-Them World – immigrants had the expected habit of brewing and drinking that which was common to them at home. The importance of beer, wine, and cider went beyond their now common use and cultural nostalgia. They were a safe source of hydration, as water in many parts of the burgeoning country was dangerous to consume. Alcohol became, for the colonists, the most important beverage as they began the process of founding the United States of America. As time passed, the need of alcohol for survival lessened and the party scene grew and became more acceptable.

Well, acceptable for a short time. The party grew too loud and the voracious consumption of brewed and distilled alcohol drove some to create the American Temperance Society. In a shocking 1832 expose of American drinking habits, the society published the fact that 72 million gallons of distilled alcohol was being consumed by Americans every year towards the end of the 1820s. With a population of only 12 million, every American would have had to drink six gallons of liquor a year – the equivalent of 30 modern bottles of the hard stuff. Considering that there were enough abstainers to create a national society, those who did drink had their work cut out for them. Men were (unsurprisingly) the main consumers, but (surprisingly) the society believed children, along with women, were quite experienced drinkers as well. Historian W.J. Rorabaugh has claimed that children learned early from their parents how to drink and what to drink. Most were taught responsible consumption and moderation, but arguably – at more than 30 bottles of liquor per drinker per year – moderation in that era was, well, less moderate. Rorabaugh wrote that “As soon as a toddler was old enough to drink from a cup, he was coaxed to consume the sugary residue at the bottom of an adult’s nearly empty glass of spirits.” By the time the Chippewa Valley grew into the Northwoods community of legend of the mid-1800s, alcohol was embedded into the American experience.

Alcohol had saturated American culture so much that the Wisconsin Territorial Statutes of 1839 required Wisconsin inns to provide an around-the-clock tavern. Inns became the primary public place to consume alcohol. Lawmakers weren’t only focused on the thirst of early Wisconsinites, but also required inns to provide beds and fodder, for horse and human alike. Under these requirements Adin Randall built one of the first inns in the Chippewa Valley, betting wisely that an inn and tavern in Eau Claire would be an excellent investment. Randall dubbed the new inn The Eau Claire House. In a short while, historically speaking, taverns and inns similar to The Eau Claire House would see their taps pouring non-alcoholic beverages or none at all.

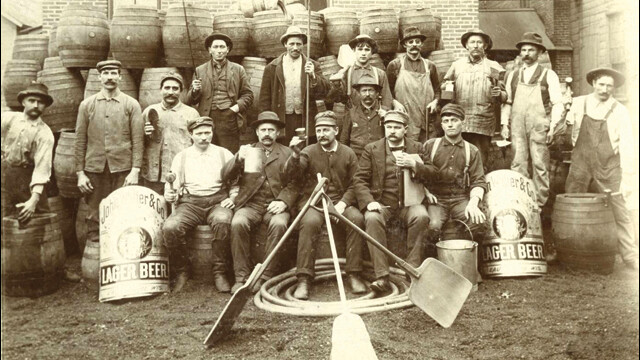

The Wets

The term "Wets" does not refer to the well-bathed or to clumsy men in a canoe, but to those saturated with alcohol, as a “dry” person would say with derision. Prior to prohibition, the typical Wet found refuge and comfort in the saloons and drinking culture of chippewa valley. As to who the Wets were, well, they were primarily the rough-and-tumble immigrants who came to the Northwoods to cut timber. Historian Madelon Powers has argued that the saloons were an important place for workingmen, immigrants, and the lower classes.

Powers also states that the saloons were pretty much welcome centers for the average immigrant. Instead of Craigslist for job-searching endeavors, a workingman who recently immigrated would toss a few back at the local saloon that catered specifically to others from the homeland. These ethnic saloons, which were by far in the majority, would also serve as a veritable Google search, providing information about confusing American customs and opportunities to take part in political discussions(1), yet face-to-face with a beer apiece.

“They simply thronged the streets of town, when off work, looking for beer and finding plenty, judging by the number of drunken men.” – Lois Barland, author of Sawdust City: A History of Eau Claire, Wisconsin from Earliest Times to 1910The best data from this period, which helps confirm Power’s assertions, comes from the saloonkeepers listed in Eau Claire city directories. Not surprisingly, the number of saloons has fluctuated drastically throughout the history of the Chippewa Valley. Starting with Adin Randal’s Eau Claire House, the numbers increased as the lumber industry took off and diminished as the lumber industry diminished.

Throughout this period – the late 1800s and the early 1900s, prior to Prohibition – two things remained constant. First were the lumbermen and other workers in the city, always thirsty. As local historian Lois Barland put it bluntly, “They simply thronged the streets of town, when off work, looking for beer and finding plenty, judging by the number of drunken men.”(2) The other constant was the saloonkeepers themselves. They were predominantly Eau Claire’s ethnic population, especially German-Americans and Norwegian-Americans. In 1880, 33 saloonkeepers operated establishments in the Eau Claire area. Out of that number, 12 were of German background, four were Norwegian, and four were Irish.(3) The rest were an assortment of other European ethnicities and not one was a bona-fide, self-identified, totally assimilated American. This trend continued well into the 1900s.

Within the “Wet” culture of Eau Claire in 1900, Norwegians and Germans reigned. By 1905, Germans and Norwegians each owned 19 percent of all saloons in Eau Claire, which isn’t too surprising considering how many of us still claim either or both of these ethnicities as our heritage. Canadians, Irish, Swiss, Austrians, and Americans owned the rest.(4) Leading into Prohibition, Norwegians would be hit the hardest, as they owned a full quarter of all saloons in Eau Claire.(5)

As would be expected, ethnic saloonkeepers typically recreated customs popular from their homelands in order to build and maintain patronage.(6) Through our research, we discovered a record book kept by an Irish saloonkeeper between 1869 and 1872 that, to the trained eye, has clearly shown that at least half of the patrons of the Tom Cruise in Far and Away-style Irish saloon were arguably of Irish descent.(7) Powers also uses this data to argue that Irish patrons went to that particular Irish saloon because it represented a distinct effort by the saloonkeeper to maintain the drinking customs of the homeland.

The adoption of the National Prohibition Act (aka the Volstead Act) by Congress in 1919 was not popular in the saloons and among immigrant groups in the Chippewa Valley. The Wets were no longer Wet, or at least not imbibing in respectable public establishments. Luckily for them and for many of us – the modern-day Wets – Prohibition did not last.

The Drys

Similar to the Wets, the "Drys" were not people who somehow avoided water and in particular somehow managed to escape the dreaded humidity that clings like a second skin. No, the Drys were in fact very preoccupied with driving society away from the bottle.

With the arrival of the saloon came the first murmurs of a temperance movement. As is typical anytime there is a new problem, the news guys got blamed, like that time in college when you had a new roommate move in and took the opportunity to notice how disgusting the place was all of a sudden. Some of the established good folk of the Chippewa Valley saw the presence of alcohol as a problem directly related to the great influx of immigrants. The new Chippewa Valley residents found themselves as No. 1 and 2 on Rev. W.W. McNain’s list of the top six reasons why there was way too much boozing:

1. People were coming west to escape restrictions on society. Those coming west represented a class who were naturally drunk.

2. Foreign populations were coming west who were strangers to temperance.

3. New types of drinks, like lager beer, were making drunkards.

4. The public craze for dancing in the west presented young men with the opportunity to drink.

5. People come west for material improvement and in the process an interest in neighbors had been lost and people became isolated either as families or as individuals.

6. Laws were not being enforced and places were selling liquor without licenses; eight to 10 in Eau Claire itself!(8)

Rev. McNain, making sure he was understood, went on to say bluntly, “Most of our villages and districts are filling up with a foreign population, the most of whom are strangers to the temperance reformation and who establish at once the breweries and beer saloons, and who in this way and others favor intemperance and other immoralities.”(9) Pretty sick burn. With the immigrant card thoroughly played as well as the beginning of a general agreement among Drys that saloons and alcohol were dangerous, people began to organize against the thriving culture of both.

Unlike the saloonkeepers, who were primarily a part of the ethnic populations and blue-collar social classes in the Chippewa Valley, the people who designated themselves as prohibitionists and temperance supporters were primarily non-immigrant Americans and were a part of the Chippewa Valley’s white-collar crowd. The first such organization was the Temple of Honor and Temperance in May 1877. They believed, wisely, that in order for temperance to work, the Wets needed to be reformed into Drys.

“The supply of alcohol would continue as long as there was a demand for liquor,” the Eau Claire News declared on Oct. 6, 1877. Whether for good or ill, the Eau Claire Daily Free Press published the names of the all officers who were nominated and would oversee the Temple of Honor and Temperance’s operations. At least seven of these 11 officers of the Temple of Honor and Temperance self-identified as Americans in U.S. census data. They were economically situated in the upper and middle classes, and this determined much of their rhetoric and policies. M.B. Hubbard, L.E. Latimer, and James Culbertson were lawyers, M.D. Bartlett was a prominent city attorney, and Hiram W. Bushnell was a reverend. Their influence and financial situations allowed the Temple of Honor and Temperance the ability to promote and support various temperance activities.

“Most of our villages and districts are filling up with a foreign population, the most of whom are strangers to the temperance reformation and who establish at once the breweries and beer saloons, and who in this way and others favor intemperance and other immoralities.” – Reverend W.W. McNain, on the influence of immigration towards the Chippewa Valley’s temperance reformationOne year into the Chippewa Valley’s temperance saga, J. Ellen Foster called for and succeeded in forming the Eau Claire chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, also known as WCTU, in 1878. The WCTU, a national organization, was intent on limiting, if not eliminating, the use of alcohol,(10) along with other social vices, such as gambling and prostitution. The WCTU’s strategic plan was to pull at the heartstrings of Americans by being mostly concerned with the protection of women and children from the detrimental actions of husbands and fathers – which, honestly, is still a legitimate reason to keep some people from drinking. This position gained widespread support from across all of society.

Much like the Temple of Honor and Temperance, the WCTU was an old-stock American organization. Annette Shaw, the wife of lumber baron Daniel Shaw, was among the first ranks of the WCTU, joining up in June 1878. Like Annette Shaw, many who joined the Eau Claire WCTU self-identified as American and hailed from the middle and upper classes. They included: Mary Tolles, wife of machinist Robert Tolles; Jessie Dudley, wife of Minister Joseph F. Dudley; Jane Putnam, wife of land agent Henry Putnam; Olive Howland, wife of school teacher Henry Howland; and Martha Wilson, wife of one of the earliest lumber manufacturers, Richard Wilson.(11) (If you feel a little miffed that these women as identified as “wife of so-and-so,” remember that historical records have not been expunged of their sexist tendencies and that at the time these women were recorded not as individuals, but as men’s wives.)

The WCTU and the Temple of Honor and Temperance were typical of other temperance groups formed during the late 1800s and early 1900s. The theme of ethnic and class divide was common, and the battles were fought between those who were American and the ethnic saloonkeepers and company. The first major success was the Volstead Act of 1919, and the war was won by the prohibitionists (for a time) when the 18th Amendment to the Constitution of the United Stated took effect in 1920, making the production, sale, and transportation of alcohol illegal. Even while celebrating the victory, the prohibitionists realized that the actual enforcement would be a daunting challenge.

The Battle Won, the War Lost

With the passing of the Volstead Act in 1919, the nation had laid the foundation to enforce the prohibition of alcohol on a national level. The Eau Claire Leader reported on a grand celebration that was to take place in light of the victory. A common thread of thought and verbal praise centered on the temperance movement’s success in creating a more American and homogeneous civilization.

“I don’t care if 47 states vote dry, we’ll fight it out to the last ditch.” – W.C. Osborn, Temperance leader

Temperance leader W.C. Osborn, not content with just the victory of the Volstead Act, declared that it was just the beginning: “I don’t care if 47 states vote dry, we’ll fight it out to the last ditch.” Even while people like Osborn celebrated and imparted passionate resignation to see the fight through to the finish, others, caught up in the warmth of victory, believed the end of the demon of alcohol had finally come. The war was over, and now it was time to relax with a nice cup of tea and watch the world fall into line with the grand visions of the perfect American culture. The celebratory rhetoric and the disdain for alcohol increased within the ranks of the temperance movement.

With the acceptance of Prohibition and the expectation of enforcement, it began to dawn on the both the Wets and Drys that despite a constitutional amendment, alcohol was not going anywhere – that is to say, it would still be entering the glasses, jugs, mouths, and throats of all willing. Alcohol’s prevalence was in part due to the fact that immigrants desired deeply to maintain the tastes and loves of their homelands. Eau Claire County’s experience was typical during Prohibition, with roughly 239 people arrested between 1919 and 1925 for breaking the Volstead Act. Approximately 50 percent of these were of foreign nationality.

A strong indicator to those who attended the “we won, now let’s celebrate with some root beers and water” party that their victory was going to be short-lived was the going out of business sales the saloonkeepers threw. On June 30, 1919, every Eau Claire saloon opened its doors and the liquor and beer flooded out. Two men carried a washtub quite a long ways to fill it up with alcohol. Another group spent $700 – roughly $9,887 today – for a barrel of alcohol. These long-term investments were indicative of the Chippewa Valley’s “Dryness.”

The Drys had their day in the sun – well, 13 years in the sun – while the Wets roguishly pushed through. Then the inevitable came, and in 1933 the Chippewa Valley was once again Wet.

~

1. Madelon Powers, Faces Along the Bar: Lore and Order in the Workingman’s Saloon, 1870-1920, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 15

2. Lois Barland, Sawdust City: A History of Eau Claire, Wisconsin from Earliest Times to 1910, (Stevens Point: Worzalla Publishing Co., 1960), 84.

3. Records of the Bureau of the Census, U.S. Federal Population Census, 1880, (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, June 1, 1880) www.Ancestry.com, (accessed on May 6, 2013); 1880 Eau Claire City Directory.

4. Wisconsin State Census, 1905; Eau Claire City Directory, 1905-1906.

5. Records of the Bureau of the Census. U.S. Federal Population Census, 1910, (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, June 1, 1910), www.Ancestry.com, (accessed on May 6, 2013).

6. Powers, Faces Along the Bar, 48.

7. Account Book, 1869-1872. Box 3, shelf B6/5d, McIntyre Library, Special Collections & Archives, University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, Eau Claire, WI; Records of the Bureau of the Census, U.S. Federal Population Census, 1870, (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, June 1, 1870), www.Ancestry.com, (accessed on January 28, 2014).

8. Eau Claire Daily Free Press, December 29, 1859.

9. Eau Claire Daily Free Press, December 29, 1859.

10. Maureen Flanagan, America Reformed: Progressives and Progressivisms, 1890s-1920s, New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 42.

11. Eau Claire Daily Free Press, November 11, 1882.