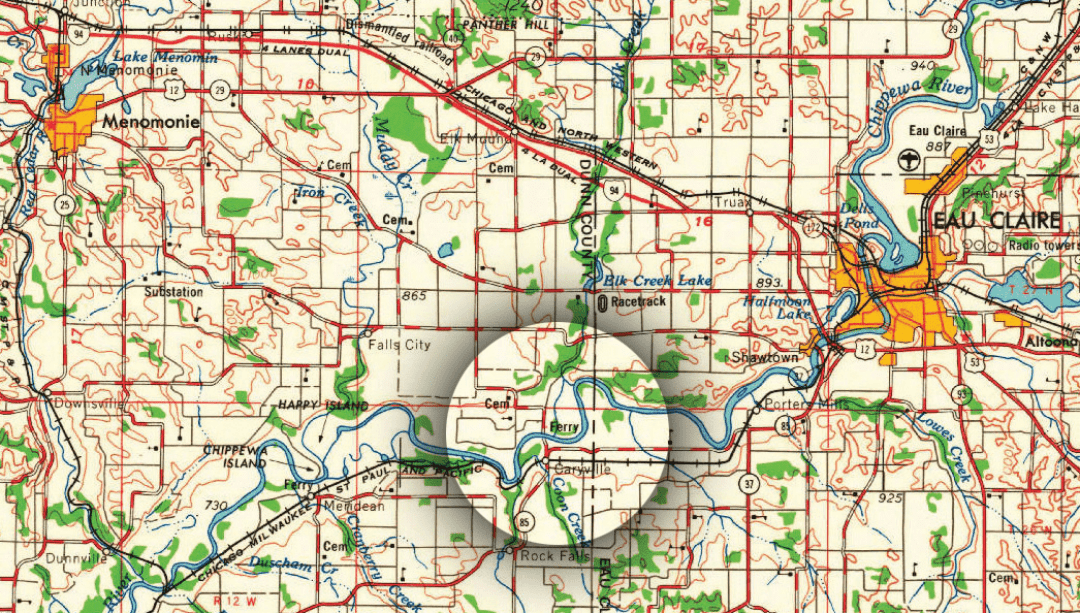

Like his assisting Rev. John Ritland on his weekly Sunday morning crossings.

Given the shortage of ministers at the time, Rev. Ritland, whose parsonage was in Caryville,

began his Sundays with a service at Spring Brook Lutheran on the north side of the river.

Directly following, Jim would ferry him back across the river so that he might repeat his sermon to the congregants at Rock Creek Lutheran.

When the current was too fast, Bill Alf and the reverend would peer out at the river together to determine the best course of action.

On one such morning when the river was at flood stage, Bill eyed the river and said, “I think the Good Lord will watch over us.”

“Yes,” Rev. Ritland eventually agreed, “but I don’t think we should stick our necks out.”

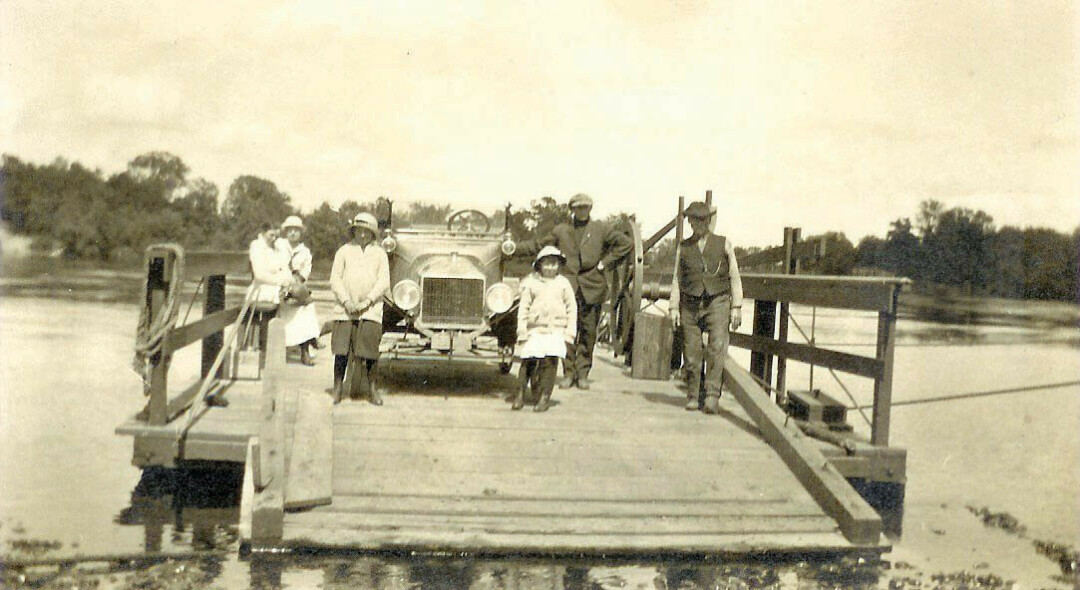

Long after midnight in June 1954, the Alfs were awakened by a far different sort of traveler.

Paying little attention to the “This Ferry Operates From 6 am to 12 Midnight” sign,

a California man and his passenger laid on their horn and demanded to be taken across the river at around 2am.

As Jim tells it, the driver reeked of alcohol.

Bill Alf was so incensed by the early morning wake-up that he said, “Mister, this is going to cost you a buck!”

“You can take your buck and you know what you can do with it!” the man hollered back.

Unaware that the ferry had left the shore, the man put his car in reverse and squealed off — directly into the river.

Soaking wet, the men waded from the car and sobered up by way of a nap in a nearby haystack.

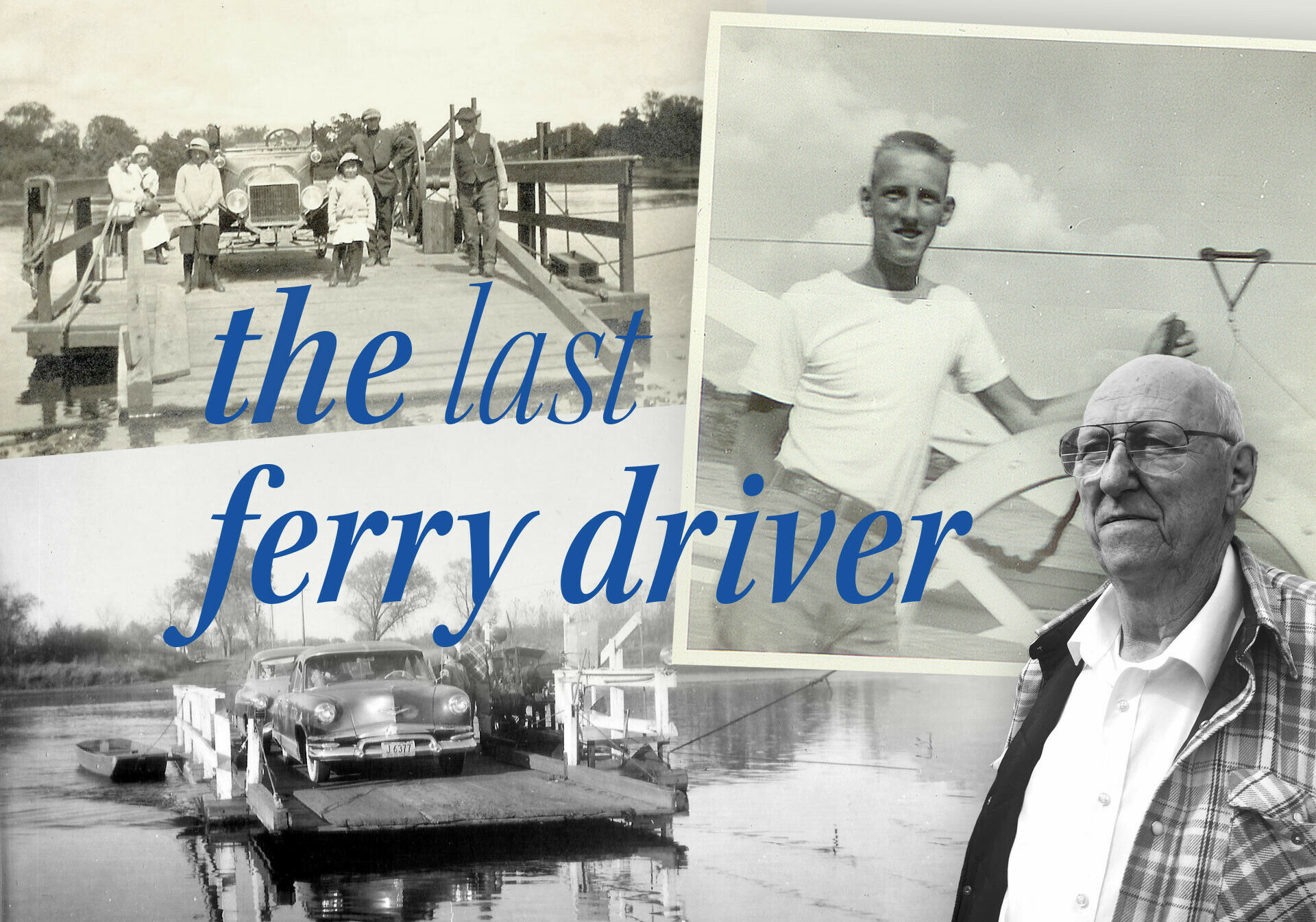

As Jim recounts in When The Ferries Still Ran —

his comprehensive account of ferry life in the Chippewa Valley —

the men were approached by Menomonie Sheriff Clarence Walters the following morning.

Since the men were no longer drunk, no charges could be filed.

“But there is one thing I can do,” Sheriff Walters told Bill Alf,

“I know the most expensive towing service in Menomonie and that’s the one I’m sending down.”